Situational Leadership for Science Teams

A flexible, adaptive approach to leadership you can start using now

Leadership training programs abound, especially for new faculty members. Becoming the leader you want to be doesn’t have to be an overwhelming, intensive experience where you have to create all new systems and change who you are. I’ve recently been reading about a style of leadership called Situational Leadership, as presented in a (very large) series of books centered around The One Minute Manager. The two I’ve read so far (below) are presented in parables, which is kind of a lovely way to learn something new. Humans learn best through stories, so I’m already a huge fan of this series and look forward to reading more. Plus, the two books I’ve read so far were about an hour of reading, so quick and easy to digest. I’m going to give a quick summary, then share some thoughts on why this could be a good model for leading science teams.

The central premise is that managers work for their direct reports, not the other way around, and are responsible for giving people the tools and resources they need to do their jobs. Further, individuals may need different kinds of leadership from their managers than others on the team. And, in fact, each individual may need different kinds of leadership for different parts of their job.

Before I dig into the model a bit, I want to quickly revisit the difference between leadership and management. The best summary I’ve seen is that you lead people and you manage tasks. I do think that in this model, the difference gets a bit lost, but I think if we stay focused on how we are interacting with our team members, I think it will become a little clearer. Maybe a modest revision would be that you lead people to manage their own tasks?

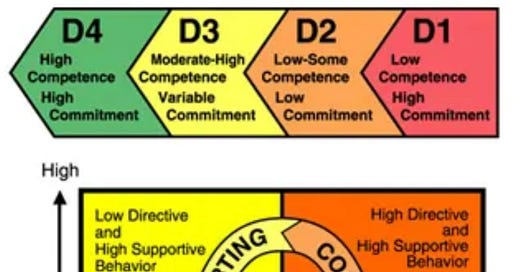

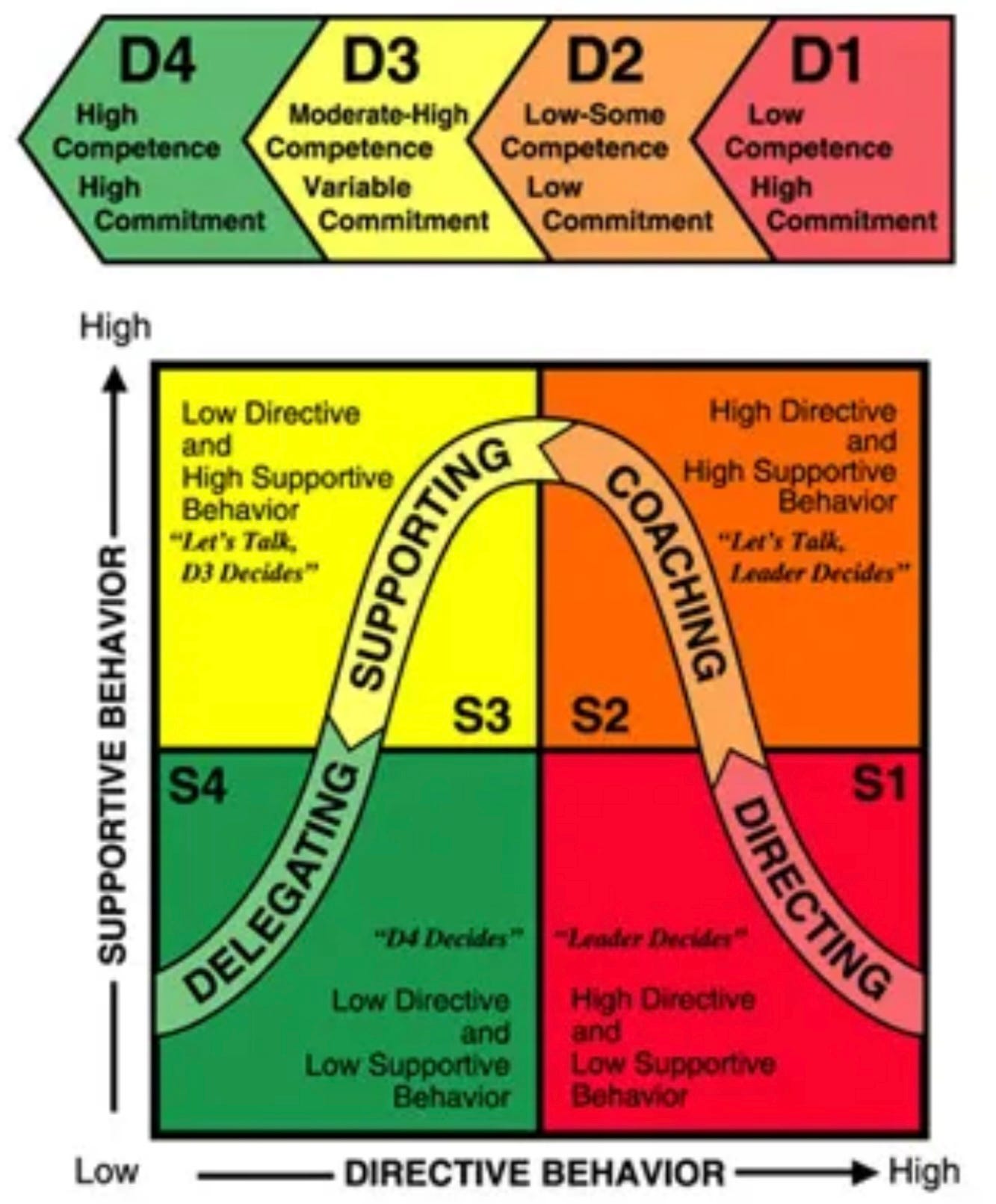

There are many versions of the model for Situational Leadership II, and I’ve included two graphics below I pulled from a quick web search. A very light summary is that team members come to their jobs (or even to sub-parts of their jobs) with different levels of competenceand commitment. The four combinations of these two characteristics can be seen in the Developmental Level of the Individual (D1->D4) in the model. Further, each of these levels requires a different kind of leadership characterized by differing levels of direction and support. Direction focuses on defining the task, what success looks like, and how to go about achieving the desired results. Support is about answering questions, helping people figure things out for themselves, and helping them feel good about the job they’re doing and their abilities.

Starting with D1, someone who is new to a position may have high levels of enthusiasm and commitment but low levels of competence. This stage is also known as the Enthusiastic Beginner. That person would require a “directing” style of leadership, in which the leader gives a lot of direction, with low levels of support. (I think this aspect of the model is a little misleading, but makes sense within the bigger picture. Obviously, you’re giving that new person a lot of support but it looks different than “support” in other levels.) Here, as the leader, it’s your job to tell the team member exactly what needs to happen, setting them up for being successful in a task where they may be unsure and not yet competent. And checking in with them frequently to provide course correction, encouragement, and further instructions as needed if they seem to be struggling.

Level D2 is characterized by low/some competence and low commitment. Here, the parables are really great at explaining what the authors mean by “low commitment.” Think back to a time when you were learning something new, like how to play an instrument or speak a new language. After your initial burst of enthusiasm (D1), you may realize how hard it’s going to be to become an expert or even competent in this new task. They call this stage the “Disillusioned Learner” and we have all been there! Here, the model suggests a leadership approach akin to Coaching, in which the leader provides high direction still (think about your piano teacher in your 2nd or 3rd year) and lots of support to help you get through the messy middle of learning the skill.

A team member in the D3 level has developed some competence but may have variable levels of commitment. They call this stage “Capable but Cautious Performer”. The team member has developed some skills but may still not be fully sure of their abilities. This person requires a “Supporting” leadership approach, in which the leader provides low direction (the person knows how to perform the task) and high support (encouragement, showing trust, serving as a sounding board). This might look like asking questions such as, How do you think you should approach this challenge? and then waiting for them to answer rather than answering for them.

Finally, someone in level D4 is called a “Self-reliant Achiever,” someone who displays high competence and high commitment. This person requires a “Delegating” leadership approach, in which the leader gives them the freedom to do their jobs or at least that particular task with full autonomy, serving as a resource in case of questions or problems.

The hope is that each of your team members will move through the levels and end up in a D4 with all of the various parts of their job! The reality is that some people may not, even with a lot of support, at which point it is time to have a conversation about whether the job is a good fit or needs to be adjusted.

This is, of course, a very simplified version of the model, and I highly encourage you to read a little more about how best to direct and support. The books describe how to have collaborative conversations to decide together what each team member’s competence and commitment are for each aspect of their job.

How does this apply to science teams? As the PI of a research team, you are the leader of that team and the buck stops with you. It’s very easy to move to a place of micromanaging even those who come to you with a high level of competence and commitment in their tasks. But that’s exhausting and unsustainable and doesn’t serve you, in the end, or them. I think it’s especially challenging for PIs who are themselves still learning a lot about how to run a research team! You yourself may be a D1 or D2 in leadership and management. Further, your team will likely consist of students, who are probably all in D1 and require a lot of directing and support, research staff who may be anywhere along the continuum, and faculty collaborators, who are quite likely in the D3-D4 range in what you’ve written them into the grant to do. Providing the wrong kind of leadership can leave team members feeling unsupported and unmotivated, costing you time and money and costing them the opportunity to grow and achieve their full human potential.

I am looking forward to trying out this model in my own work relationship to see how it lands with others. I really like the flexibility it provides in meeting people where they are AND that it emphasizes where they are is ok as long as they are committed to working together toward greater competence. It provides a way to have conversations that are value-neutral instead of judgmental.

Please share your thoughts below in the comments, on my LinkedIn page, or via email at theteamsciencelab@substack.com.

Got a question about team science? Subscribers can email me at theteamsciencelab@substack.com, and I may answer your question in this space!

Figures credit: https://discover.hubpages.com/business/What-is-the-Situational-Leadership-Theory

Titles I’ve read so far:

Leadership and the One Minute Manager (Blanchard, Zigarmi, and Zigarmi)

Self Leadership and the One Minute Manager (Blanchard, Fowler, Hawkins)